Happy Spring Equinox! A good day to share the news that I have started a traineeship with Growing Communities. Between now and the end of October, I will be spending a day a week learning as much as I can about regenerative and organic food growing practices by helping out at Growing Communities’ market gardens in east London.

I am VERY excited about this; I have been gently nurturing the possibility of moving my life towards agroecology for a few years now, and this feels like the first tangible step in that direction.

I first experienced the joy of growing food with my grandparents — specifically my granddad on my mum’s side, and my nan on my dad’s side: both keen gardeners with a particular interest in growing food. School holidays were split between them, and I have fond memories of helping each of them in their gardens — with my granddad, carefully peering through what felt like forests of clambering runner bean vines to find and pick the ripe pods, and listening and looking with rapt attention while my nan showed me how to tell when different varieties of tomato are ready for picking. As I got older, I lost touch with this joy. I lived in London and my parents weren’t particularly interested in growing food, so aside from the times I spent as a smaller child with my grandparents at their respective homes in Dorset and Cardiff, I grew up mostly detached and disengaged from the who, where and how stories of the food on my plate.

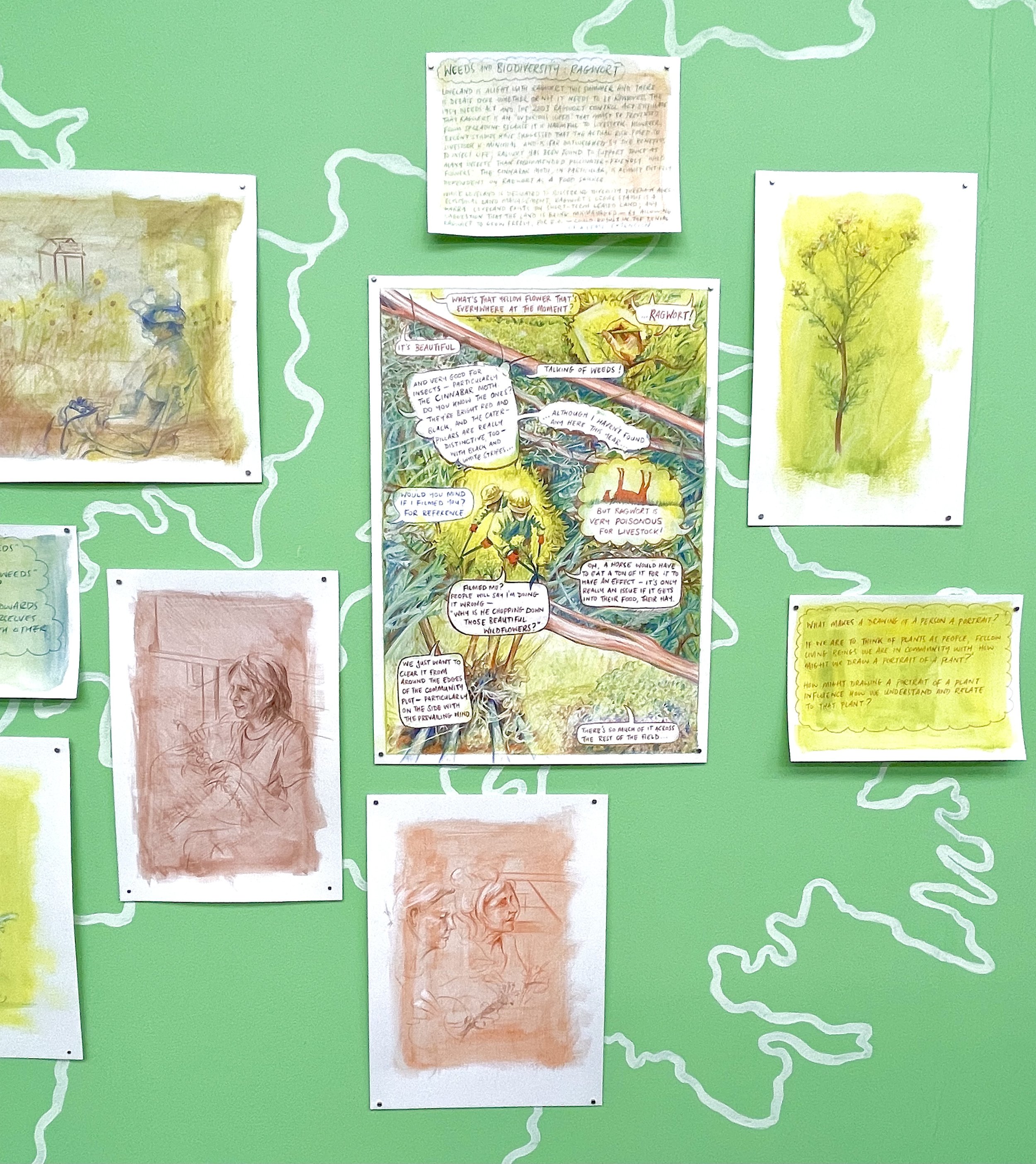

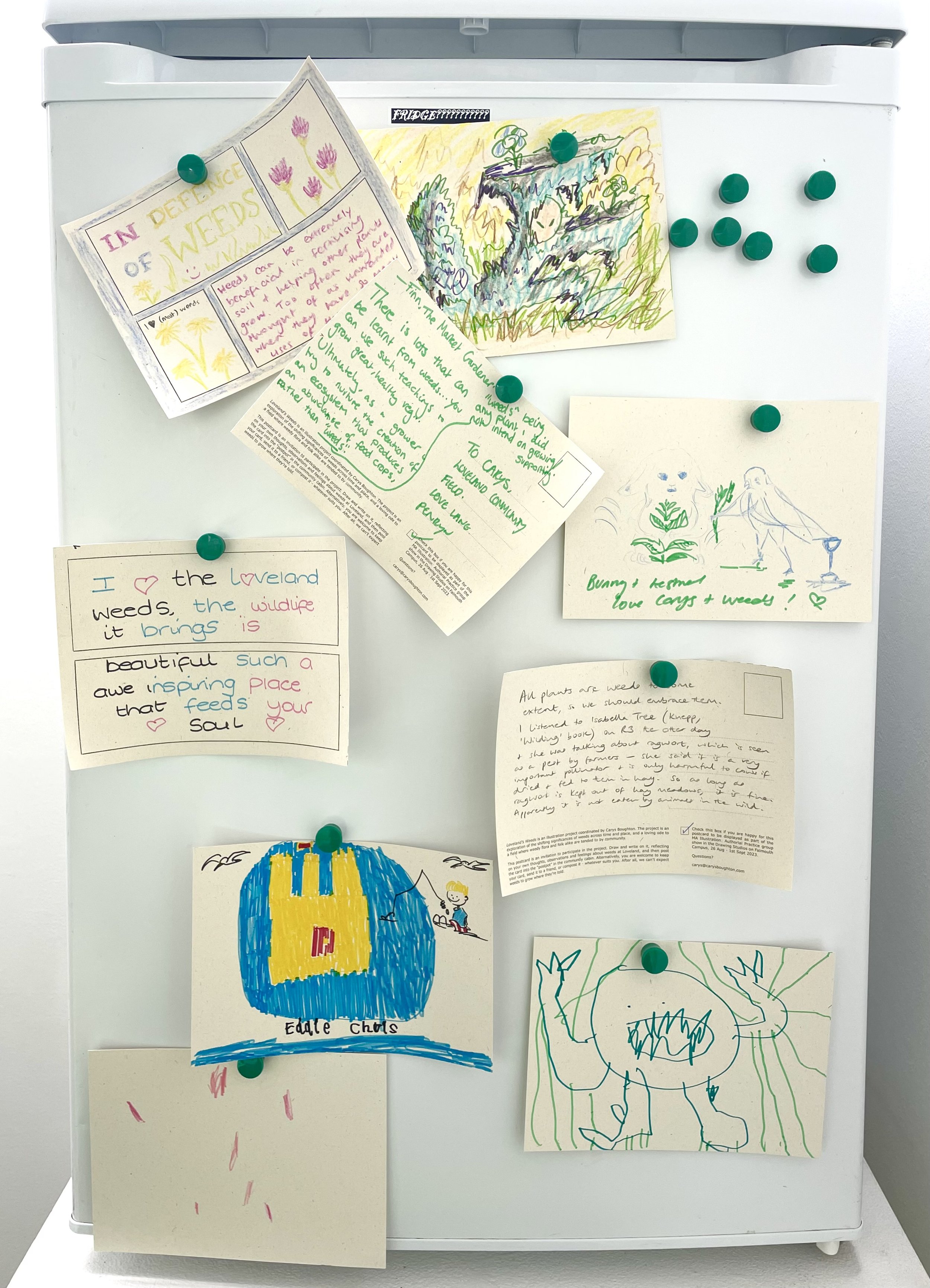

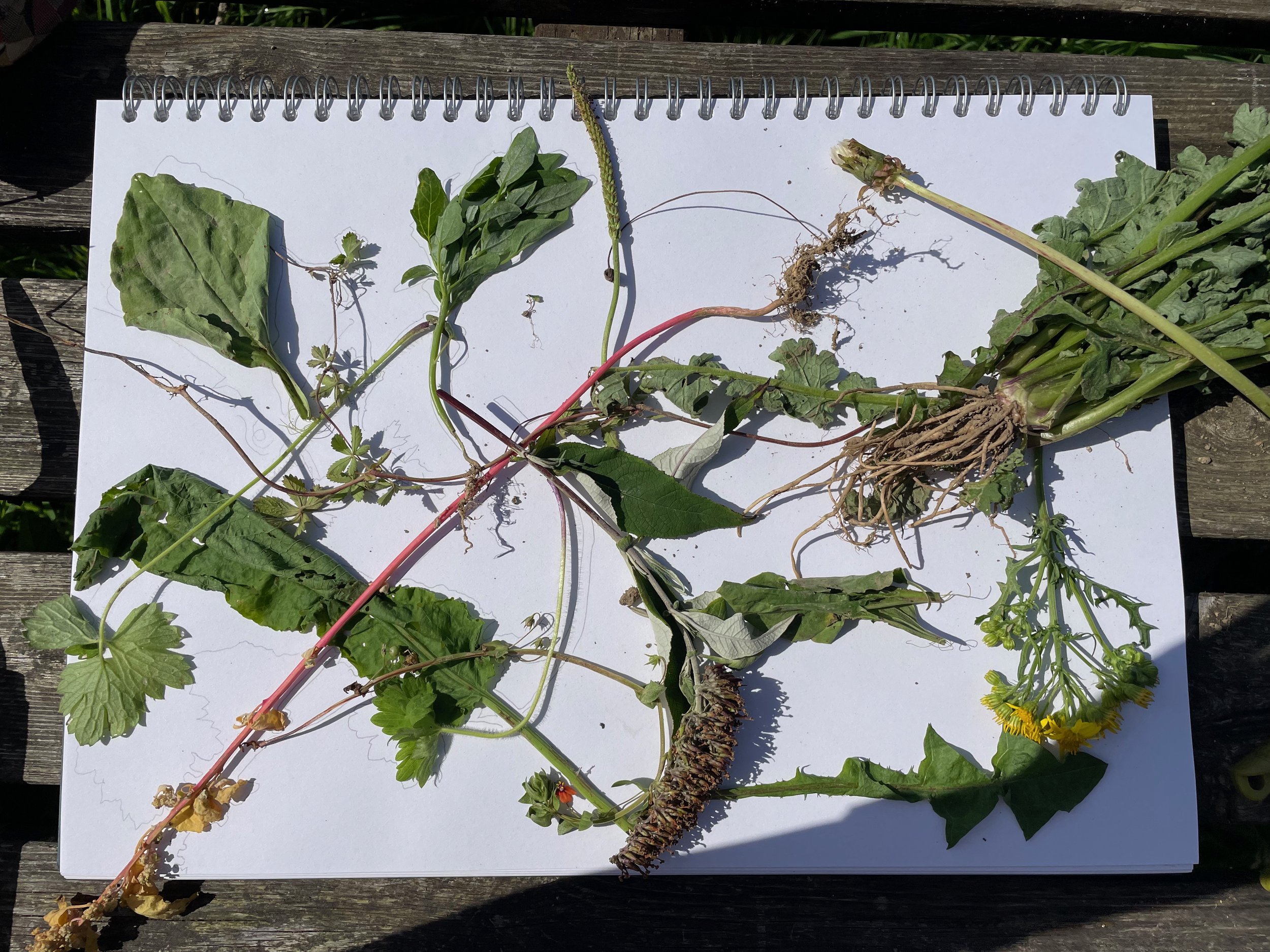

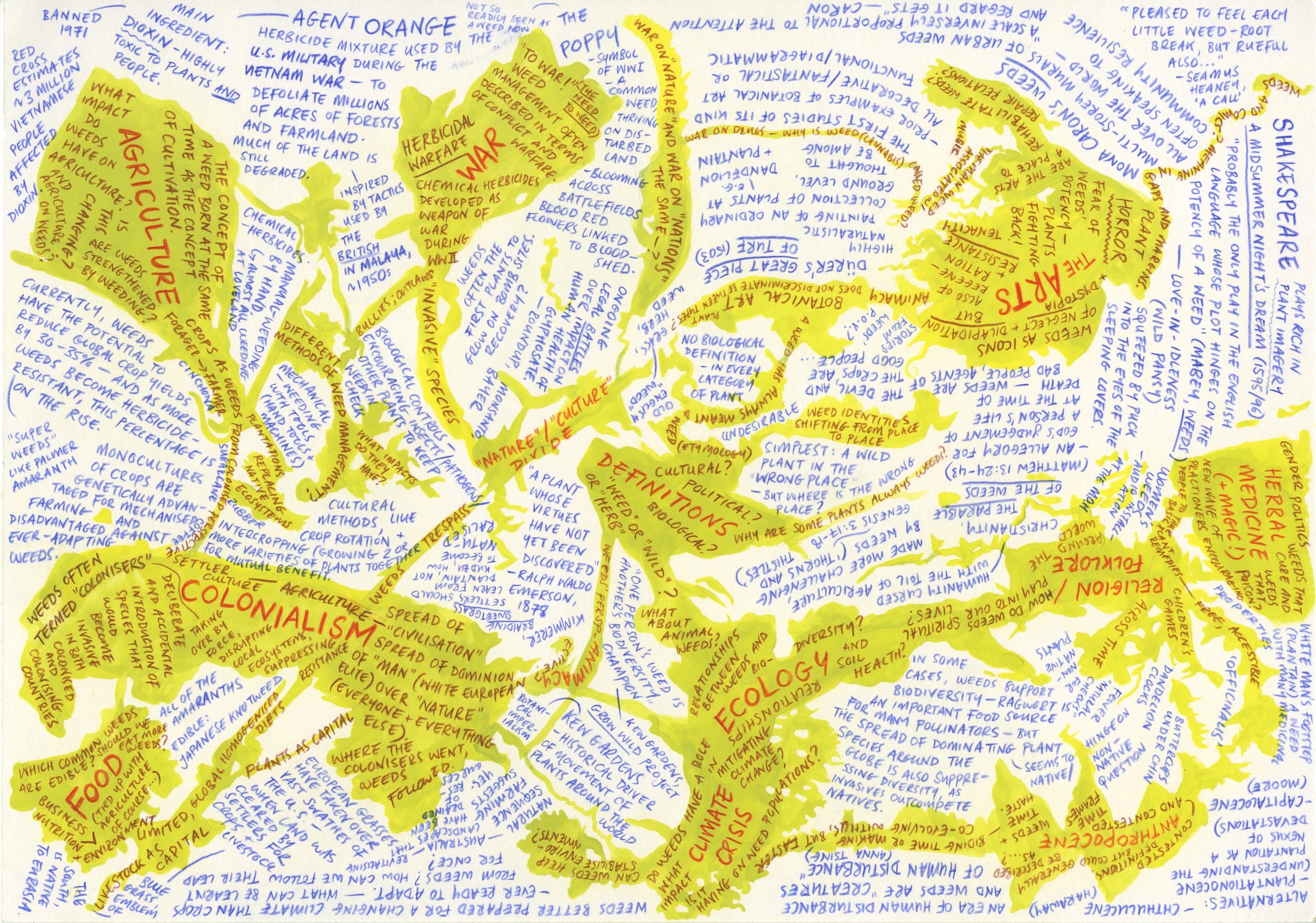

In my early twenties, my involvement in climate activism and the illustration work I was doing for multiple charities tackling modern slavery and forced labour drew my attention towards the problems and injustices inherent in the globalised, industrialised food system. At the time, I responded to this by making changes to my diet and where I sourced my food (I started buying a veg bag from Growing Communities..!) and trying to encourage others to do the same. However, it wasn’t until I moved to Falmouth to start my MA in illustration, that I reconnected with the practical joy of growing food —and with it a deeper motivation to contribute to better food systems — by getting involved with a local community growing project. I started volunteering at Loveland Community Field in the hope of making new friends and alleviating some academic stresses by spending time outdoors; I had not anticipated that I would fall completely in love with community food growing, and that this love would call me to shift my life towards agroecology. This began with me spending as much time at Loveland as I could, learning the basic principles of agroecological food growing from the market garden leader and other volunteers, and relishing sharing the magic of growing and eating the food we had grown together. Then this progressed into focusing my MA work on Loveland and food growing — documenting in drawing the activities of the volunteers, and then creating comics to explore the relationships between the human people of Loveland and the plant people of Loveland, engaging with decolonial theory and Indigenous knowledge systems to interrogate the colonialism-rooted divide between “Nature" and “Man” that is the foundation of industrial agriculture and all its damaging effects (see this post about my Loveland’s Weeds project).

When I moved back to London in December 2023, I was determined to find a way to continue to nurture the joy and passion for community food growing that had ignited in me at Loveland. So I looked for volunteering opportunities and, in the meantime, started trying to grow food at home, while continuing to explore food growing themes in my personal illustration practice. A few months later, I started volunteering with Growing Communities, and over the course of the nine months since then, my interest and excitement has only grown. The more I learn, the more I realise I don’t know and the more I want to learn. I am drawn in by every aspect of the world of agroecology – from the studies into the benefits of regularly being in touch with soil for our gut microbiomes, to the grassroots battles taking place across the world to protect heirloom seed varieties from corporate patent capture. I am determined now to channel more of my energy and attention into this world, so that I may begin in earnest to create a life that will bring about a valuable contribution to it.

Visualising the possibilities of a future with food growing at its heart makes me feel like that kid again, steeped in the wonder of the gifts grown in my grandparents’ gardens. I’m really excited to be following that joy, and hope to spread it among as many people as I can.

The dream is to find ways to bring together growing and illustration practice to inspire and support more people to question and disrupt the dominance and violence of industrial agriculture; and to imagine and create together better food systems that bring us all into healthier relations with our ecosystems. (I’ll keep you posted on how that develops…)

In the meantime, I hope to share my experience of this traineeship through a weekly quick comic, documenting a slice of each day spent on site. Here’s the first! I will post the others to my instagram as and when.